The Ethical Perils of AI Content Detection

Introduction

The recent emergence of advanced generative AI (e.g., OpenAI’s ChatGPT) has transformed writing and research by producing fluent, human-like text on demand. Launched in late 2022, these tools were quickly adopted by students, professionals, and the public, sparking urgent debates in academia and policy. In response, some startups appeared with their “AI content detectors”, promising to distinguish AI-generated text from human-authored content. Schools and publishers in particular rushed to adopt these tools, fearing that students or writers would use AI to cheat or plagiarize. Yet the reliability of such detectors is questionable, and their widespread use raises hard questions about accuracy and fairness.

This article examines two core questions: (1) How accurate are current AI content detectors, and what are their limitations? and (2) What ethical and policy issues arise from relying on these tools?

Fallibility of AI Content Detectors

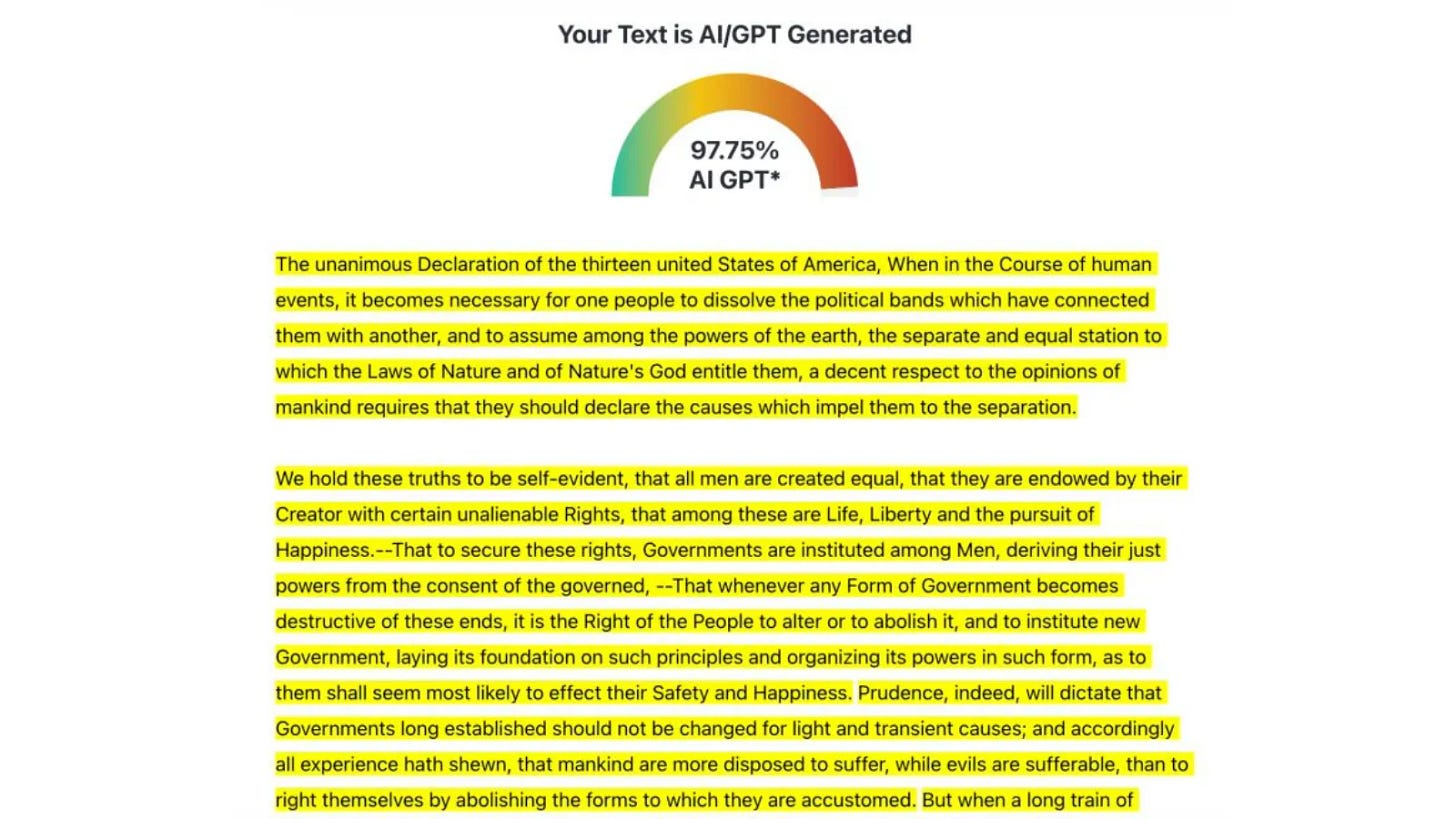

AI text detectors suffer from alarmingly high error rates. Numerous tests have shown that even well-written human texts can be mislabeled as AI-generated (false positives), while sophisticated AI outputs sometimes evade detection (false negatives). For example, a recent analysis by Decrypt found that popular detectors wildly misclassified the U.S. Declaration of Independence: one gauge (see Figure below) rated the 1776 text as 97.75% AI-generated.

Other tools similarly “totally boffed it,” falsely flagging classic literature and academic abstracts as machine-written. In one educational study, detectors showed inconsistencies on genuine student essays, generating false positives and “uncertain classifications” for ordinary human-written work.

Such glaring errors illustrate how detectors can produce absurd results. In practice, simple paraphrasing or synonyms can let AI-generated text slip through undetected, while any text lacking unusual vocabulary or complex grammar (often characteristic of learning-language writing) can be flagged as “AI.” In fact, OpenAI warns that detectors have a tendency to misinterpret writing by non-native English speakers as AI-written. In short, these tools operate as black-box probabilistic models. They scan for statistical patterns rather than true semantic ownership, so their outputs cannot be trusted as conclusive evidence. The lack of transparency compounds the problem. Many detectors do not disclose their algorithms or error rates, making it impossible for users to judge reliability or bias. A Vanderbilt University guidance document reports that Turnitin’s new AI detector was disabled after school administrators realized even a 1% false-positive rate could mislabel hundreds of students’ work as AI-generated. Leading education technologists similarly advise against high-stakes use. MIT Sloan teaching lab guide emphasizes that AI detectors have “high error rates” and can lead instructors to falsely accuse students. They note that OpenAI itself shut down its own ChatGPT classifier due to “poor accuracy”. In short, detectors often fail spectacularly in practice, confirming that they are far from a reliable policing tool.

Ethical and Human Rights Concerns

Beyond technical flaws, automated detection raises serious ethical and rights-based risks. False positives can unfairly harm individuals, violating principles of fairness and due process. Already there are reports of students facing academic penalties based on detector scores: one educator recounted a Turnitin alert flagging 90% of an international student’s paper as AI-written, leading to an urgent meeting to justify the work. This is not a hypothetical risk; biased detector errors can threaten grades, scholarships, and even immigration status for foreign students. As one student noted, “An AI flag can affect my reputation overall.” Such consequences are alarming in democracies where educational access and reputational rights should be protected. Relying on opaque algorithms to judge writing quality smacks of surveillance: it can chill student expression and disproportionately penalize those with different linguistic or cultural backgrounds. A Stanford study found seven popular detectors mislabeled non-native English writing as AI-generated 61% of the time, while almost never making the same mistake on native English papers. As one researcher explained, “The design of many GPT detectors inherently discriminates against non-native authors”. This is because AI text tends to use common words, the same patterns non-native speakers often do. Thus a tool designed to find AI style may inadvertently flag just those students who are less fluent. The result is unfairness and a potential class or nationality bias: an immigrant student could be accused of “cheating” purely because their writing resembles algorithmic style. In broader social terms, deploying unreliable detectors in civil or legal contexts could undermine democratic values. Imagine using an AI detector as evidence in a court or university tribunal: one’s liberty or career might be jeopardized by a flawed statistical tool. Without transparency or recourse, this contravenes principles of due process and human dignity. International human rights frameworks emphasize that people have the right to receive fair treatment in education and legal settings; casting suspicion algorithmically could violate those rights. Given these risks, we must be extremely wary of institutionalizing AI flagging as a compliance measure. Such outcomes violate basic equity and educational ethics.

Policy Recommendations

Given the shortcomings of detection, this article proposes shifting policy toward constructive, rights-respecting approaches.

First, education systems should prioritize AI literacy and curriculum reform over bans. International frameworks, such as UNESCO’s new AI competency guidelines, urge teaching students and teachers to understand AI’s capabilities and limitations. Embedding AI topics across subjects (not just computer science) can cultivate a human-centered mindset and ethical awareness. For example, assignments could integrate AI tools for brainstorming or language-checking, accompanied by instruction on evaluating AI suggestions. Schools should train teachers to guide critical dialogues about AI (consistent with UNESCO’s human-rights emphasis) rather than hiding it. Clear AI usage policies, transparently communicated, can replace silent suspicion with explicit expectations. This approach harnesses AI as a learning aid while honoring intellectual integrity.

Second, there should be institutional governance principles that safeguard fairness. Detection software should never be the sole basis for punitive action. Any AI flag should trigger a full human review, not an automatic penalty. Universities and publishers should treat detector results as supplemental at best, and should require corroborating evidence (e.g., discussions with the author). The reason is because many users understandably distrust black-box algorithms. Transparency is crucial. Institutions should demand that vendors publish accuracy metrics, error rates by demographic group, and clear explanations of how scores are derived. Where possible, open-source or peer-reviewed detection tools could improve accountability. In legal or disciplinary contexts, explicit prohibitions on admitting such scores as evidence, much as a fair court would reject an unreliable lie detector.

Third, there should be academic and educator support rather than punishment. Instead of penalizing students for AI usage, schools should incorporate AI into pedagogy. Examples include requiring students to submit AI-assisted drafts with annotations, or using in-class writing assessments that evaluate thought process as well as result. Providing guidelines on responsible AI citation (the APA and MLA have issued style rules) and building assignments around personal experience or current events can limit misuse. Having students reflect on AI as a tool can foster intrinsic motivation and ethics without heavy-handed surveillance. Finally, policymakers should invest in research on “AI for education” that helps students learn, rather than just policing them.

Fourth, a rights-based public policy approach is needed. Governments and institutions should affirm that automated detection may implicate due process and nondiscrimination rights. Legally, students should have the right to contest AI flags and to appeal decisions. Schools ought to frame AI concerns as part of broader academic integrity policies, not as covert technological policing. On a national level, regulatory agencies might issue guidance (similar to how privacy laws emerged) on fair use of algorithmic decision tools in education. Under no circumstances should private data (like student essays) be sold or used beyond educational purposes. AI detectors often require uploading text to third-party servers, raising privacy issues. Policies should prioritize empowerment (AI literacy, support) over enforcement (algorithmic detection).

Conclusion

AI-generated text detection is, in the end, a flawed and probably fleeting technology. Its many false positives and opaque operations make it ill-suited for high-stakes judgments about human authorship. Like the calculator fears of the past, current alarm over AI writing will pass as society learns to integrate the tool rather than demonize it. The focus should shift from adversarial policing to critical engagement: teaching students how to use AI ethically, sharpening curricula to demand creativity, and defending fairness in educational governance. By embracing rights-based principles and robust AI literacy, policymakers can turn the challenge of generative AI into an opportunity for more honest, inclusive learning. Rather than chasing the mirage of perfect detection, institutions should foster an environment where technology amplifies, not undermines, human development.